Please check out the new resource: In the Spirit of the Circle

Episcopal Women’s Caucus

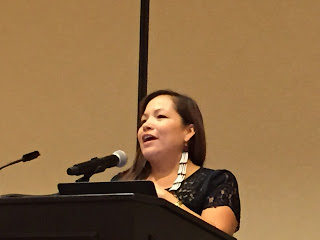

Keynote by Sarah Eagle Heart

June 29, 2015

Cante Waste ya Nape Ciyu zape ye. My name is Sarah Eagle Heart, my lakota name is Wanbli Sina Win or Eagle Shawl Woman in Lakota. I grew up on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.

I am the Missioner for Indigenous Ministry and I have been blessed to witness leadership in a variety of ways in the Episcopal Church. I have been blessed to be supported in my leadership by key leaders and especially by women. That support is truly a gift, I will never forget all the days of my life becauseI didn’t want to be a leader. Beginning when I was seventeen years old, I was actively trying to get out of it. Sometimes, I still try to get out of it. Being a leader is difficult, which is why I often share my story so other young leaders who step forward will know leadership is truly a calling. For native people, leadership includes a sense of responsibility for the whole community.

I intimately know the socioeconomic and justice issues indigenous people must face in order to persevere. I often share my own experience of childhood on one of the most poverty-stricken communities in the United States to educate. All my life I have felt as if I walked in worlds of cultural duality. I grew up one mile outside a small white farming town of 1100 inhabitants, in a tribal community in the LaCreek District of Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. The town of Martin, South Dakota is located between two Indian reservations in South Dakota. This unique interracial environment allowed for an early introduction to race, class and power dynamics. Fortunately, I had strong role models, determined Lakota women, raise us with traditional Lakota values and taught to live our cultural values inherently and give back to our people.

The first settlers carried with them the belief of the Doctrine of Discovery, which relied on a fifteenth-century document by the pope (called a Papal Bull) that gave Christian explorers the right to claim lands they “discovered” for their Christian monarchs. Land not inhabited by Christians was available to be “discovered” and claimed. If the “pagan” inhabitants could be converted, their lives might be spared.

The idea of Manifest Destiny guided the colonization of North, South, and Central America—a racist belief that European settlers were “destined” to claim land from coast to coast. This attitude guided the behaviors that pushed western expansion and promoted the forced removal of Native Americans from their traditional homelands.

In the name of God, the Indigenous people of this land were forced from their homes and made to walk the Trail of Tears. Many died, both along the journey and when they reached the reservations (also known as prison camps). Many tribes, cultures, and languages were decimated on these long,

forced marches. The very last goal set by the government was assimilation of “Indians.”

Indigenous tribes were not given enough food to eat, and they caught diseases from the European immigrants. Many Indigenous people died from illnesses like smallpox, but the colonists also killed many people in cruel and inhumane ways. In a 2012 pastoral letter, Presiding Bishop Katharine Jefferts Schori decried the Doctrine of Discovery: “These religious warrants led to the wholesale slaughter, rape, and enslavement of indigenous peoples in the Americas, as well as in Africa, Asia, and the islands of the Pacific, and the African slave trade was based on these same principles. Death, dispossession, and enslavement were followed by rapid depopulation as a result of introduced and epidemic disease.”

In 2009, The Episcopal Church became the first denomination in North America to repudiate the Doctrine of Discovery, and acknowledge our role in this shameful era of human history. Presiding Bishop Katharine Jefferts Schori said, “This is also a matter for healing in communities and persons of European immigrant descent. Colonists, settlers, and homesteaders benefited enormously from the availability of ‘free’ land, and their descendants continue to benefit to this day. That land was taken by force or subterfuge from peoples who had dwelt on it from time immemorial—it was their ‘promised land.’ The nations from which the settlers came, and the new nations which resulted in the Americas, sought to impose another culture and way of life on the people they encountered. Attempting to remake the land and people they found ‘in their own image’ was a profound act of idolatry.”

The work of the Repudiation of the Doctrine of Discovery continues our commitment to the 1997 Jamestown Covenant by exposing the wrongs done “on behalf” of Native Americans through the brutal settlement and conquest of the Americas. The Episcopal Church does not omit the past but instead stands in solidarity with Native Americans and Indigenous people, advocating

for the oppressed and praying for the oppressors. Today, missionary work does not strive to assimilate but to raise local leaders for reconciliation through healing, contextual education, empowerment, and advocacy. The strength of The Episcopal Church is the ability to stand in the tension of shame and guilt, facing it with Jesus at our side and acting through the Baptismal Covenant to strive for peace and justice.

Due to the loss of our foundation of traditional Indigenous teachings of cultural identity, the result has been a loss of trust for humanity… sadness, despair and anger has taken its place on many reservations. Many of our indigenous communities in North America have become numb and struggle to connect with who they really are, a beautiful people with cultural riches beyond what anyone can imagine in this contemporary day, and what they are capable of achieving.

This is where a theory of healing and action was born. The theory that healing and education provides an avenue for communities to reconcile and come together for action. Ministries such as Navajoland, Alaska, North Dakota and South Dakota have begun to pick up the pieces and revitilize language and culture with youth. These mission areas actively work with to combat the suicide epidemic, gathering leaders for healing and theological education.

Those who do the vulnerable work of healing: feel a need to rebalance society, learn to forgive, learn to trust and begin to dream again. This is an individual and communal rewiring of possibility. This is transformational point of intersection is where truly meaningful, long-term intergenerational grassroots action can occur.

We are now at a place where we are beginning to see the fruits of healing and action. It’s time to target communities to network, leverage excitement and momentum to map assets, assess needs, identify key stakeholders, develop timeline and budget, and designate a team of community managers. Vital to the success includes key leadership, flexibility, continuous feedback, improvement and ongoing evaluation.

Key indicators for success include: White Earth Ojibwe Tribal Chairwoman Erma Vizenor implemented White Bison’s teachings on intergenerational trauma in tribal juvenile detention system and saw a 70% decrease, reservation demographics indicate half of population to be under the age of 18 years and Tribal youth are raised with Lakota/Dakota/Nakota values of: Wacantognaka (generosity), Wotitakuye (kinship), Woksape (Wisdom) and a sense of communal responsibility “to help your people”. Indigenous youth desire to learn and connect with their culture. Identification with culture leads to emotionally stable, dedicated, communally driven leaders. Reservation Community Development Enterprises, such as Thunder Valley, are being developed with 20-year strategic plans to build eco friendly housing and healthy communities. Access and affordability of organic foods is essential as life expectancy is drastically lower within indigenous populations. This is a place ripe for healthy community development.

I am inspired by the people I meet working collectively to build better communities: White Bison, Inc., a non-profit known for teachings on intergenerational trauma due to boarding school era, became the first example of a cross sectional partnership demonstrating a major denomination could support healing, traditional spirituality and cultural revitalization. Another example is the recent partnership between the Episcopal Diocese of South Dakota and the White Buffalo Calf Women’s Society for domestic violence prevention through a Domestic Foreign Missionary Society New Opportunity Grant. As well as the work that Bishop’s Native Collaborative theological education and training funded by an Domestic Foreign Missionary Society Indigenous Theological Training Grant.

To plan for seven generations, we have to continuously foster relationships with youth and young adults. It has been my joy to help young adults discern leadership direction through programs like Why Serve, the Young Adult Discernment Conference for People of Color. To see them excel as speakers here as deputies and preaching makes me proud beyond measure.

The moments that have stayed with me since becoming a missioner include spontaneously funny and deeply spiritual occasions… praying at Good Shepherd Mission in Navajoland and feeling ancestors all around me; laughing with Cornelia as she put on her collar for the first time, seeing my friend Cathlena get ordained knowing how hard she worked to be able to attend seminary, the moment Catharine gave me a turquoise ring to symbolize her support, receiving a blanket from the Diocese of South Dakota with Terry honoring ministry work, talking to Bishops about history of the church with Native Hawaiians, listening to a group of women spontaneously sing in their traditional language to us over video conference, or standing in Lake Pyramid with Paiute women as Reynelda blessed me with sage and water.

These moments come by spending time in relationship with people serving Indigenous Ministry. These moments are a gift not only to me, but for the whole church teaching of generosity, selflessness and humility. Of a people still hurting, but still resilient. Reminding us that it is not just about you or me, but about all of our relations. Mitakuye Oyasin. Amen.

No comments:

Post a Comment